Stinging nettles show up right when you need greens most. We’re talking early spring with cool air and damp ground. Brush a plant and you’ll feel the sting. Heat it, and you get tender, mineral-rich leaves that taste like greener spinach.

This guide walks you through where nettles grow, how to identify them, how to harvest them responsibly, how to remove the sting, and the best ways to cook and store them.

What are stinging nettles?

The plant most people mean by “stinging nettles” is Urtica dioica. It grows upright in clusters. The stems and leaves have tiny hairs that cause a quick sting on your skin and, for some reason, it can even cause a skin rash. Those hairs break down with heat or drying, meaning cooked nettles don’t sting. The leaves are deep green, lighter on the reverse side, with a serrated edge, and usually grow in opposite pairs on the stem.

Because stinging nettles have a square stem and, at first glance, looks a bit like mint, for many years it was believed they were related. Now we know they’re not even distant cousins.

Where nettles grow

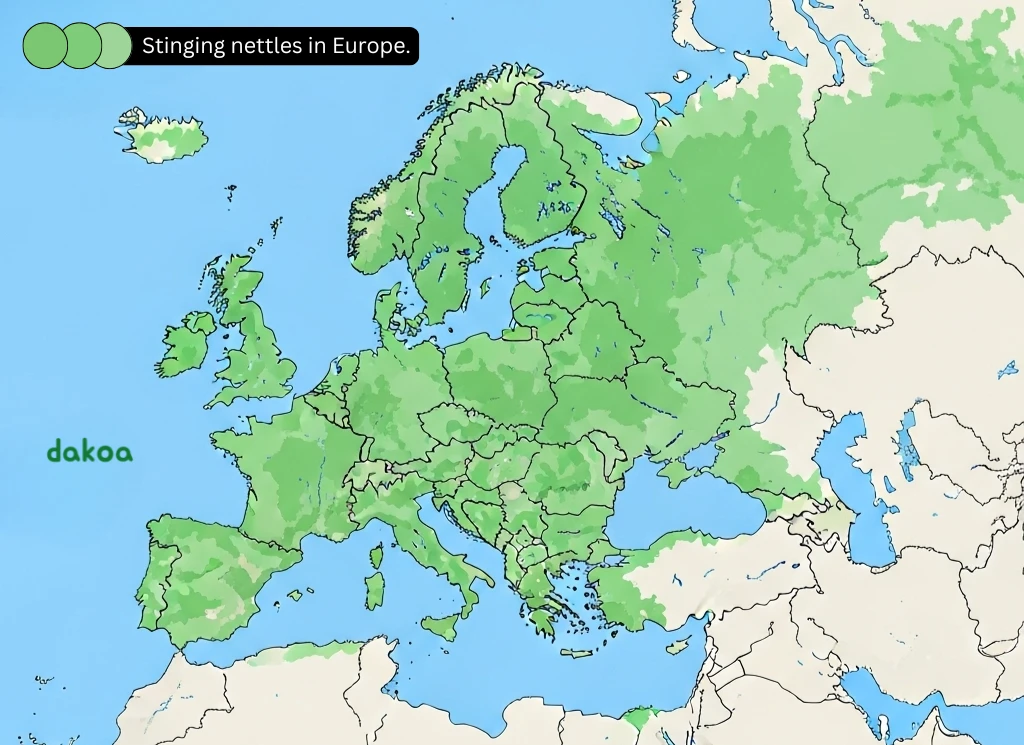

You can find nettles across much of North America and Europe. They like damp, rich soil and steady spring rain.

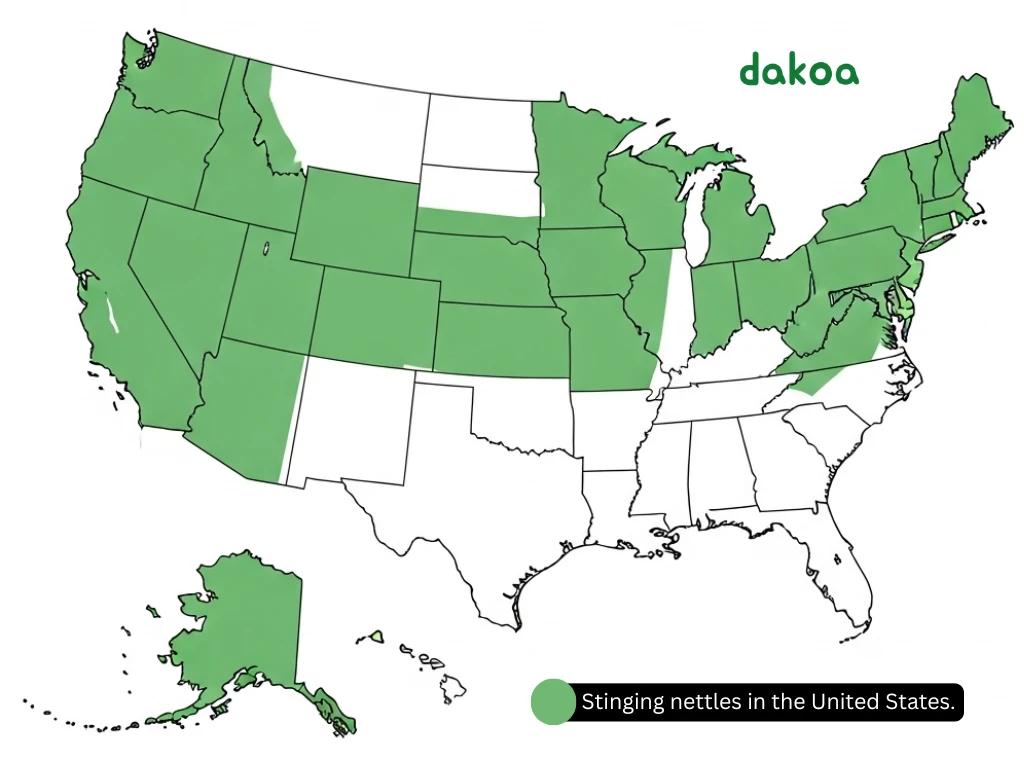

United States and Canada

You’ll find good patches in the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast, the Upper Midwest, the northern Rockies, and the Appalachian region. They also appear in many irrigated valleys in the West, where irrigation keeps soil moist. Suffice it to say, nettles like to stay hydrated. These are not full sun-loving shrubs.

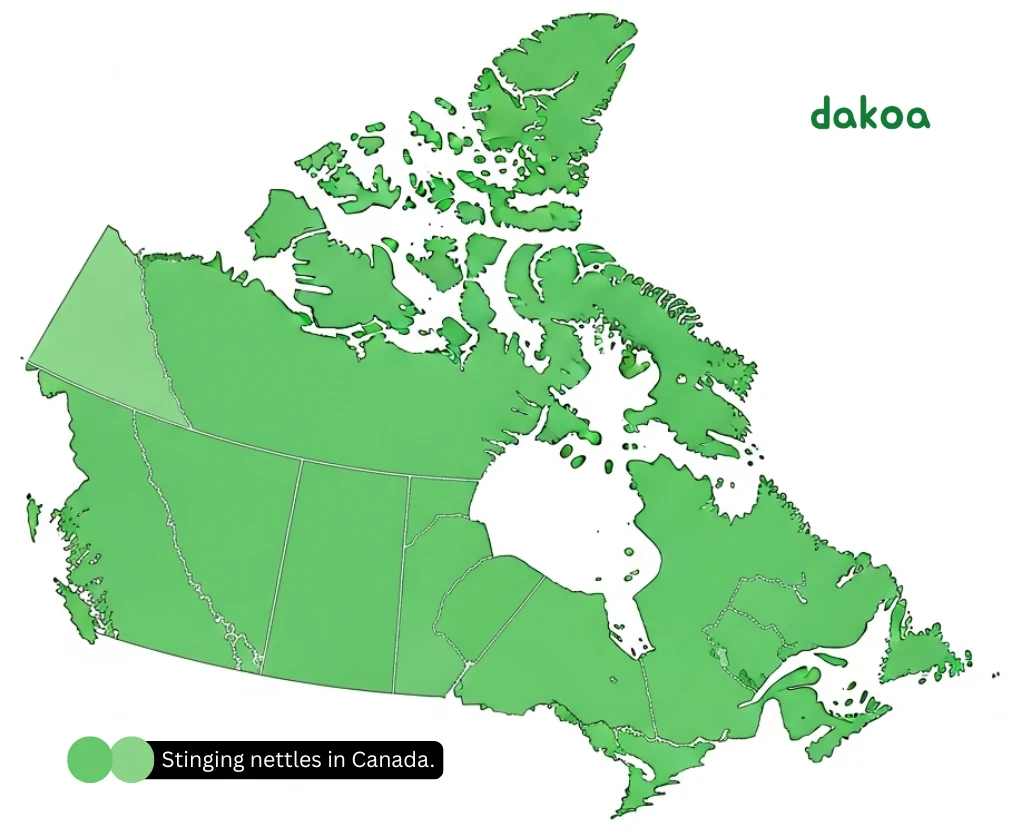

As far as Canada is concerned, you can find nettles in province and territory, with one exception, Nunavut.

Europe and the UK

When to forage

Go in spring while plants are young and tender.

- Southern U.S.: February to April.

- Mid-Atlantic and Midwest: March to May.

- Northern states and southern Canada: April to June.

- UK and much of Europe: March to May.

Pick the top few inches. That’s where the best texture and flavor live. Older plants get tough and collect grit.

How to identify nettles (and what people confuse them with)

You’re looking for three simple signs that work together:

- Opposite leaves with a toothed edge.

- A firm, ridged stem.

- Fine hairs on stems and leaves that sting when brushed.

Now the common mix-ups and how to tell them apart, along with a photo of each leaf to help you visually distinguish between the two. Giant hogweed is the most dangerous of this group, fortunately, it’s also the easiest to identify. If the leaves are huge, walk away!

Wood nettle (Laportea canadensis)

It can sting too and is also edible. Its leaves often grow in an alternating pattern rather than in pairs. If you’re in eastern forests and see “nettles” with alternating leaves, that’s likely wood nettle. Young tops cook up great.

Dead nettle (Lamium purpureum and Lamium galeobdolon)

No sting at all. Leaves can look similar at a glance, but the plants often have small purple or yellow flowers and a softer feel. They’re edible but mild and a bit weedy in flavor.

False nettle (Boehmeria spp.)

No sting. The leaves may resemble nettles, but the lack of stinging hairs and slightly different flowers give it away.

Giant hogweed and other sap-burning umbellifers

These aren’t nettles and look very different once you step back. They have huge, divided leaves and umbrella-shaped flower heads. Still, it’s good to say out loud: if you’re unsure, stop and re-check. Don’t harvest on guesswork. Giant hogweed can cause intense burns.

Crush a small leaf between gloved fingers and smell it. Nettles have a fresh, green smell that’s a little like spinach and green tea. The “sting + opposite leaves + serrated edge” combo is your best check.

| Trait | Stinging Nettle Urtica dioica Stings |

Wood Nettle Laportea canadensis Stings |

False Nettle Boehmeria cylindrica No stings |

Dead-nettle Lamium spp. No stings |

Giant Hogweed Heracleum mantegazzianum Phototoxic sap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall look | |||||

| Growth habit / first impression | Tall, upright patches; serrated, pointed leaves; visible stinging hairs on stems/leaves. | Single stems or loose clumps in shady woods; broader leaves; fewer but present stinging hairs. | Herbaceous, smooth look; no stinging hairs; often in wet spots. | Low, patch-forming mint; soft, hairy leaves; showy hooded flowers (white or purple). | Massive, towering plant; huge lobed leaves; umbrella-like white flower clusters. |

| Leaves | |||||

| Arrangement | Mostly opposite (may appear alternate near tips). | Distinctly alternate. | Often opposite (can be sub-opposite); no stinging hairs. | Opposite (mint family), soft and non-stinging. | Huge, deeply lobed, alternate; single leaf can exceed 1 m (3+ ft). |

| Shape & edge | Ovate to lanceolate; sharply serrated edges; pointed tip. | Broad, ovate; sharply toothed; often asymmetrical base. | Ovate to lanceolate; toothed; surface smooth. | Heart-shaped; scalloped/serrated; often variegated (cultivars). | Coarse, jagged lobes with deeply incised margins. |

| Stems & hairs | |||||

| Stem feel / hairs | Noticeable stinging hairs (urticating); green, ridged. | Stinging hairs present but sparser; tender stems. | Smooth; no stinging hairs. | Square mint-type stems; soft hairs; no sting. | Hollow, ridged; often purple-blotched with coarse bristles; no stinging hairs but caustic sap. |

| Flowers | |||||

| Type & timing | Greenish drooping clusters (late spring–summer). | Drooping panicles; greenish (summer). | Inconspicuous greenish spikes (summer). | Showy hooded blooms (white or purple) spring–fall. | Huge white compound umbels up to 60+ cm (2 ft) across, early–mid summer. |

| Size & season | |||||

| Height (typical) | 0.6–2 m (2–6.5 ft). | 0.5–1.5 m (1.5–5 ft). | 0.3–1.2 m (1–4 ft). | 10–40 cm (4–16 in). | 3–5 m (10–16 ft) at maturity. |

| Forager’s season notes | Best as young spring shoots; older leaves can be tough. | Young spring tops (handle carefully). | Not typically foraged. | Young tops/flowers sometimes used as mild edible/tea. | Do not forage. Avoid contact at all stages. |

| Habitat | |||||

| Common sites | Rich soils, edges, disturbed ground, fencerows, streamsides. | Shady, moist woodlands; along creeks. | Wetlands, ditches, floodplains. | Lawns, beds, field edges, waste places. | Streambanks, roadsides, disturbed soils; invasive in some regions. |

| Handling & risk | |||||

| Contact reaction | Immediate sting/tingle; usually short-lived. | Sting similar to stinging nettle. | No sting. | No sting. | Severe phototoxic burns after sun exposure; scarring possible. |

| Safe processing | Gloves to harvest; blanch/cook/dry to neutralize sting. | Gloves; cook like nettles. | Not commonly used. | Young parts can be eaten raw/cooked; confirm ID. | Do not harvest. If contacted: wash, cover from light, seek medical advice. |

| Fast tells (field checks) | |||||

| Quick ID tip | Opposite leaves + obvious stinging hairs; serrated, pointed leaves. | Alternate leaves + stinging hairs. | No sting; smooth feel; wet habitat. | Square stems, opposite soft leaves, showy mint-type flowers; no sting. | Very large size, purple-blotched hollow stems with coarse bristles, massive white umbels. |

How to harvest (with care for people and pollinators)

Nettles feed you, but they also feed wildlife. A light touch keeps the patch healthy. Please be a responsible forager!

Quick rules that work:

- Wear gloves and use clean scissors.

- Take only the tender top 4 to 6 inches.

- Spread your harvest across the patch. Don’t strip any one area.

- Leave plenty behind for insects and regrowth.

- Skip plants near roads, sprayed lawns, run-off ditches, or industrial sites.

Why it matters (because it does):

Butterflies and other insects use nettles for food and shelter, especially later in the season when flowers and larvae appear. A “little-from-many” harvest keeps the stand strong and supports that life cycle. You’ll get better nettles next year, too.

How to remove the sting

Heat fixes it. Rinse well, then:

- Blanch: Drop into boiling water for 60 to 90 seconds, then drain.

- Sauté: Cook in a hot pan until the leaves wilt.

- Dry: Dehydrate or air-dry clean leaves for tea; drying also removes the sting.

Once heated or dried, nettles are safe and gentle.

Flavor and easy ways to cook nettles

Cooked nettles taste clean and earthy with a hint of nuttiness. Keep the cooking simple, don’t overcomplicate the dish, and you’ll taste the difference.

- Garlic sauté: Olive oil, a chopped clove of garlic, blanched nettles, salt, and a squeeze of lemon.

- Nettle soup: Onion, potato, stock, and blanched nettles. Blend smooth. Finish with a bit of cream or yogurt.

- Pesto: Blanched nettles, olive oil, garlic, nuts, and a sharp cheese if you use dairy. Freeze leftovers in small cubes.

- Eggs and grains: Fold chopped nettles into omelets, frittatas, risotto, or a warm grain bowl.

- Tea: Dried leaves steeped for 5 to 7 minutes. Clean, mineral taste.

Nutrition and health notes

Nettles bring vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin K, calcium, iron, magnesium, and potassium. They also offer plant protein and chlorophyll. Many people notice they feel “lifted” after a nettle meal, which makes sense: you’re getting real minerals from a fresh spring green.

A quick caution: If you take blood thinners or other prescription medications, check with your doctor before drinking strong nettle tea on the regular. Or, at the very least, start with food-level portions like a handful of nettles on a salad and see how you feel.

How to clean and store

Cleaning: Soak leaves in cold water for a minute, swish to release grit, lift them out, and repeat if needed. Don’t pour the dirty water back over the leaves.

Fridge: Fresh nettles keep 3 to 4 days wrapped in a damp towel in a container or bag.

Freezer: Blanch, squeeze out extra water, and freeze in one-cup bags.

Pantry: Dry young leaves for tea and store in a sealed jar away from light.

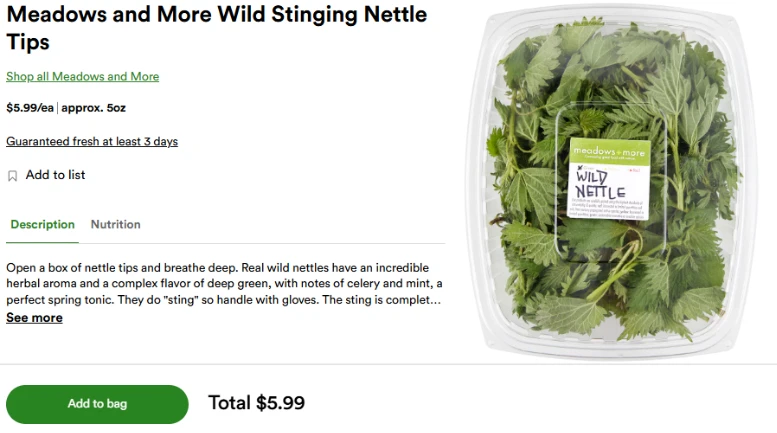

Buying and selling nettles

Some farmers’ markets carry nettles in spring. Prices vary, but you’ll often pay a premium for clean, young tops because they wilt fast and are difficult to harvest.

If you plan to sell foraged foods, check your local rules first. Some areas require permits or limit sales to approved sites. Keep your harvest cold and clean and deliver the same day if you’re working with restaurants.

Based on overall averages during nettle season, a pound of nettles can get as much as $30, when sold direct as a sustainably foraged product. Of course, a pound of nettles by weight, is a decent amount of nettles!

Common problems beginners face (and how to fix them)

My nettles taste dull.

You probably overcooked them. Keep blanching short and sautés quick.

Do I have to cook them before using?

Yes! Stinging nettles have to be processed in some way to purge all those tiny hairs covered in irritating chemicals that cause stinging. Cooking is the most common way to deactivate the sting. A quick blanching, sautéing, boiling or three-minute steam will make them safe. But you can also freeze dry the nettles to remove the sting.

They’re gritty.

Rinse, soak, and lift the leaves out of the water. Don’t skip the second rinse if your patch is sandy.

They still sting.

You didn’t heat them enough. Give them another quick blanch or wilt them fully in the pan.

I’m not finding any.

Move to wetter ground. Follow streams, shady fences, and compost-rich edges. Ask gardeners and farmers where moisture lingers in spring. And if you’re foraging in South Central Texas, you’re out of luck!

More To Discover

- 3 Ways Farmers Can Use AI Right Now To Overcome Modern Agribusiness Challenges

- The World’s Cleanest Electric Snowmobile: A Pininfarina Collaboration

- How Solar and Battery Storage Advances Are Powering Change in Africa and 2024 Will Be Even Better

- Nestle, Kellogg’s and Colgate Palm Oil Supplier Deforested 50 Square Miles Of Peru’s Amazon Rainforest

Can I just swap out nettles for mint or basil or spinach in recipes?

Yes. It’s really that easy. A one to one ratio will get the job done in any recipe. If your pesto recipe calls for 2 cups of fresh basil, swap it out with stinging nettles.