You can turn careful foraging into real income. Chefs pay for flavor they can’t buy from distributors, and they pay for local with sustainability they can boast about. 100% locally foraged is 100% sustainable, and that’s just good marketing!

Farmers’ market shoppers line up for spring greens, ramps, and morels. And local herbal shops want clean, traceable plants. The opportunity is real — but so are the rules.

This guide gives you straight answers on what sells, how to price it, where to sell it, and the permits and food-safety steps that keep you legal and insured.

What actually sells and for how much

Prices swing with weather and location, but these recent figures show the market you’re entering.

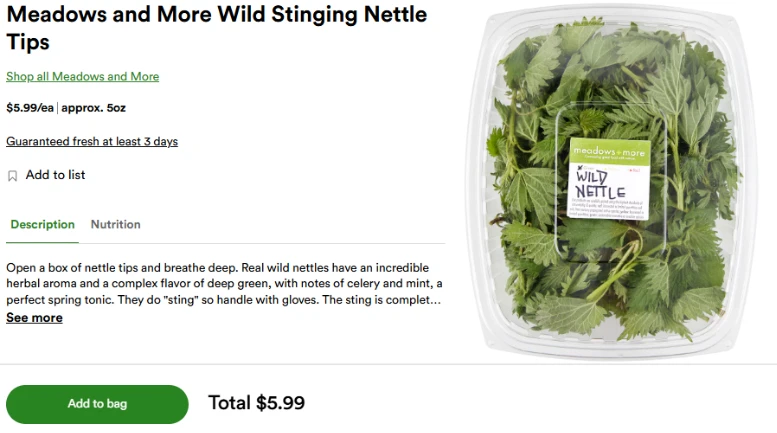

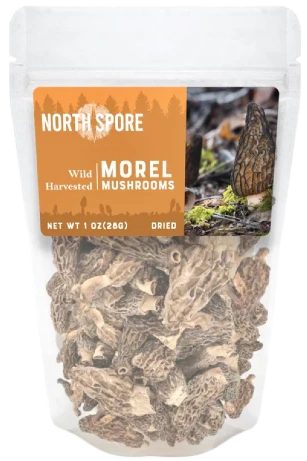

Recent U.S. wholesale reports put fresh morels near $28–$29 per pound; retail in hot weeks often runs much higher. Dried morels commonly fetch the equivalent of $160 per pound because water weight is gone.

U.S. wholesale averages sat around $16–$19 per pound in 2023–2024, while specialty retailers list fresh chanterelles at $26–$35 per pound when supply tightens.

Farmers’ markets and specialty purveyors commonly post \$20–\$30+ per pound during peak season in U.S. cities.

U.S. retail for good grades often lands around $50–$65 per pound, with export-quality lots commanding more.

Market prices vary by region, but clean, young tops sell at a premium because they’re delicate and time-sensitive.

These numbers tell you two things.

First, wild foods can beat steak on price.

Second, you need a plan for freshness, quality, and proof of legal harvest, because premium buyers expect all three. If you expect to charge a premium price, you must deliver a premium service.

Where to sell and what each buyer expects

Restaurants and specialty grocers

This is where the best margins live if you can deliver consistent quality. Expect to provide a simple invoice, your contact info, the harvest date, and species name for each lot. Many health departments require that wild mushrooms come from an “approved source,” which often means the forager or the inspector is a certified identification expert and the product is tagged with species, harvest date, and location. Several states publish their rules or fact sheets and enforce the FDA Food Code’s wild mushroom provisions at the local level.

Farmers’ markets

Rules vary, of course. Some markets allow wild foods only with documentation or proof of legal harvest; many don’t allow cutting or processing on site unless you have a food-service permit; some require wild mushroom approval or forager certification. Check the market’s vendor handbook before you apply.

Direct-to-consumer online

It’s possible to sell dried non-hazardous items (for example, dried mushrooms or your own tea blends) where cottage-food laws allow it, but shipping fresh wild foods is complex and may require additional licenses. All 50 states now have cottage-food programs for shelf-stable items, yet each state sets its own limits, caps, and labeling rules.

The legal basics you must know

Think in three layers: where you picked it, who you’re selling it to, and what the product is.

1. Land access and harvest permits

- National forests and many state forests treat mushrooms, boughs, and similar materials as “special forest products.” Personal picking is often allowed in small amounts, but selling usually requires a commercial permit. Several forests now issue permits online with clear pound limits and species rules.

- BLM lands also require forest-product permits for commercial harvests.

- Parks and preserves often ban foraging outright. A famous example is Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which prohibits ramp harvesting after research documented declines; fines can be steep.

- Private land requires permission. Intertidal seaweed laws are especially local. In Maine, the state’s highest court ruled rockweed on the shoreline is private property, so harvesters need the landowner’s permission.

2. “Approved source” and the FDA Food Code

Restaurants and retailers can only buy foods from approved sources under the FDA Food Code adopted by most states. For wild mushrooms, the Code says you can’t sell or serve them at retail unless the establishment has specific approval (typically tied to a certified identifier and documentation). States implement this in different ways, but the theme is the same: no anonymous buckets of mushrooms at the back door.

3. State-level mushroom rules

States handle wild mushrooms differently. Michigan, North Carolina, and others explicitly require that each mushroom sold to a restaurant be inspected or sourced from a certified identifier, with species lists and tagging requirements spelled out. Expect to show your certificate or your inspector’s sign-off when you sell to a licensed kitchen.

The Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO) maintains a public hub linking to state wild-mushroom regulations.

4. Cottage-food and value-added items

If you want to sell shelf-stable value-added products like dried mushrooms, teas, or spice rubs, check your state’s cottage-food law. Every state has one, but the allowed foods, sales caps, and venues differ. “Food freedom” bills in some states are expanding what’s allowed, but many still restrict refrigerated items and wholesale.

Product safety, traceability, and insurance

Your reputation is your business. Put simple systems in place from day one.

- Tag every lot. Write species, harvest date, general location, and your name on a tag or label. Several states require this for wild mushrooms, and chefs appreciate the transparency.

- Keep a harvest log. Record patch notes, weather, and who bought which lot. If a buyer calls with a question, you’ll have the answers.

- Use clean tools and containers. Brush in the field. Pack into breathable carriers. Chill promptly if the product needs it.

- Get liability insurance. Many restaurants and markets ask for a certificate. Your local farm bureau or small-business insurer can quote a basic product-liability policy.

- Know when you’re processing. Once you start pickling, canning, or vacuum-packing wild foods, you’re beyond raw produce and into a different regulatory lane. That usually requires a licensed kitchen and additional training.

Pricing and unit economics that actually work

Price by the pound, but think per hour. How many pounds can you pick and deliver at peak quality?

- Wholesale vs. retail. Chefs buying boxes expect a lower price than farmers’ market shoppers buying a half pound. In exchange, you move volume in one stop and build repeat business.

- Grade your product. Button chanterelles and firm porcini caps command more than bruised or bug-nipped specimens. Dried trumpets, powdered morels, and ramp salts are ways to use, trim and extend inventory where allowed.

- Anchor to current markets. Use current wholesale trackers and specialty retailers to set your baseline, then adjust for freshness and distance. Recent U.S. wholesale figures for morels and chanterelles — roughly $28–$29/lb and $16–$19/lb, respectively — are good reference points; your local retail may run higher in short weeks.

If you can’t harvest, clean, and deliver within 24–48 hours at a price that pays you at least a solid hourly rate after gas and supplies, switch to a dried or shelf-stable product that fits your state’s cottage-food lane, or focus on a different species that’s in season.

Conservation and ethics that protect your income

You’re not just selling food; you’re managing a renewable resource that pays you every year if you harvest lightly.

- Ramps and wild leeks. They’re slow to recover. Many parks ban harvest, and some regions protect them outright. If you do harvest where it’s legal, cut one leaf from many plants rather than digging bulbs, and stay within local rules. Over-harvesting kills both the patch and your business. In case you weren’t aware, ramps are also known as wild garlic. Wild garlic and store-bought garlic are very different.

- Seaweeds. Rules are hyper-local. Maine’s rockweed case shows why you can’t assume the shoreline is “free for all;” in Maine, the rockweed on intertidal land belongs to the adjacent landowner. Get permission in writing before you cut.

- Mushrooms. Cut or cleanly twist, don’t rake the forest floor. Follow permit pound limits and stay off fragile slopes after heavy rain.

Just harvest in a way that lets you come back next year and still find abundance. That’s what makes you a real forager!

Real-world paths to your first sale

1. Sell nettle tops to a local restaurant.

Bring a one-page sheet with your harvest practices, a sample bag kept cold, and a proposed price by the pound. Offer a standing Thursday delivery for the next four weeks. Nettles are an easy gateway: quick to identify, fast to clean, and a chef’s friend in soups, pastas, and pestos.

2. Supply chanterelles to two chefs only.

In season, commit to just two buyers you can keep stocked. Grade and box carefully. Text the night before harvest with expected pounds. Show up on time with tagged lots. Chefs reorder from reliable foragers.

3. Dried products under cottage-food rules.

If your state allows dried mushrooms or teas, build a line of 1–2 ounce jars with clean labels, species name, weight, and “packed on” date. Sell at markets with samples in a small grinder. Dried trumpets and morel powder are flavor powerhouses and carry you through winter.

Frequently asked questions

Do I need a permit to sell wild mushrooms?

If you’re harvesting on public land and selling, almost certainly yes. National forests and many state forests require commercial or special forest product permits. Separately, restaurants are usually barred from buying wild mushrooms unless they come from an approved source with certified identification and proper tags. Check your state’s adoption of the FDA Food Code and any state-specific rules.

Can I sell foraged foods at a farmers’ market without a commercial kitchen?

For raw, unprocessed produce, the answer is often yes, but markets set their own rules. Many prohibit on-site processing and require approval for wild mushrooms. Ask for the market’s vendor policy and talk to your local inspector before opening day.

Can I ship wild foods I picked?

Fresh products are tricky because of perishability and interstate rules. Dried, shelf-stable items are more realistic where your state’s cottage-food law allows it. Read the fine print on allowed foods, sales caps, labels, and whether online sales are legal in your state.

What about liability?

Get product-liability insurance. Many buyers will ask for a certificate. Keep harvest logs and lot tags so you can trace every sale.

How do I set a fair price?

Start with current wholesale ranges for your species, then adjust for your grade, speed to market, and whether you deliver. Recent benchmarks: morels ~$28–$29/lb wholesale, chanterelles ~$16–$19/lb wholesale, ramps ~$20–$30+/lb retail in many cities. Always check current local prices and be ready to shift as the season changes.

What if a state bans a species?

Follow the law. Quebec, for example, protects wild leeks, and parks like the Great Smoky Mountains ban ramp harvest to protect populations. Your business only works if the resource survives. True pro-level foragers are fully committed to sustainability, and that’s appealing to customers.

The five-step launch plan

- Choose a legal patch and species. Get written permission or the right permit and start with something abundant and simple to ID. You can easily build up your foraging business from here but start simple.

- Set up your safety file. Keep copies of permits, any ID certification, sample labels and lot tags, and a harvest log template. If your state uses a certified-identifier list for mushrooms, complete the course.

- Line up two buyers. One chef and one market is enough at first. Ask what format they want (whole, trimmed, bunched) and what days they order and maintain the relationship. You’ll be surprised how quickly one satisfied customer can bring additional business your way with just word-of-mouth.

- Price for sustainability. Your pricing should include fuel, time, and gear, then add your profit margin and always grade honestly. Offer seconds (damaged or less attractive products) at a discount for stock and soup.

- Deliver like a pro. Clean, chilled, on time, with a printed tag listing species, harvest date, and your info. Text your buyer a photo when you’re on the way.

If you do those five things and keep your paperwork tight, you’ll outcompete most casual foragers on professionalism alone, and you’ll build those long-lasting relationships that you will keep you in business for years.

More To Discover

- Puzzle-Inspired Electric Minivan: Where Modular Design Meets Sustainability – Ugly Yet Promising

- Revolutionizing Fabric Recycling: New Method From Denmark Could Transform the Clothing Industry

- Farmers Are Shouldering The Burden: The Hidden Cost of Big Food’s Green Push & Every Way It Hits Smaller Farms

- How Media’s Single-Use Mask Bias Contributed to PPE Pollution During The Pandemic

Final words

Selling wild foods can be a beautiful side income or the start of a serious business.

Respect the ecosystems, know your permits, keep your records clean and up to date, and show up like a pro.

Do that, and the forest will pay you back with repeat orders, chef relationships, and a reputation that lasts beyond one perfect season.