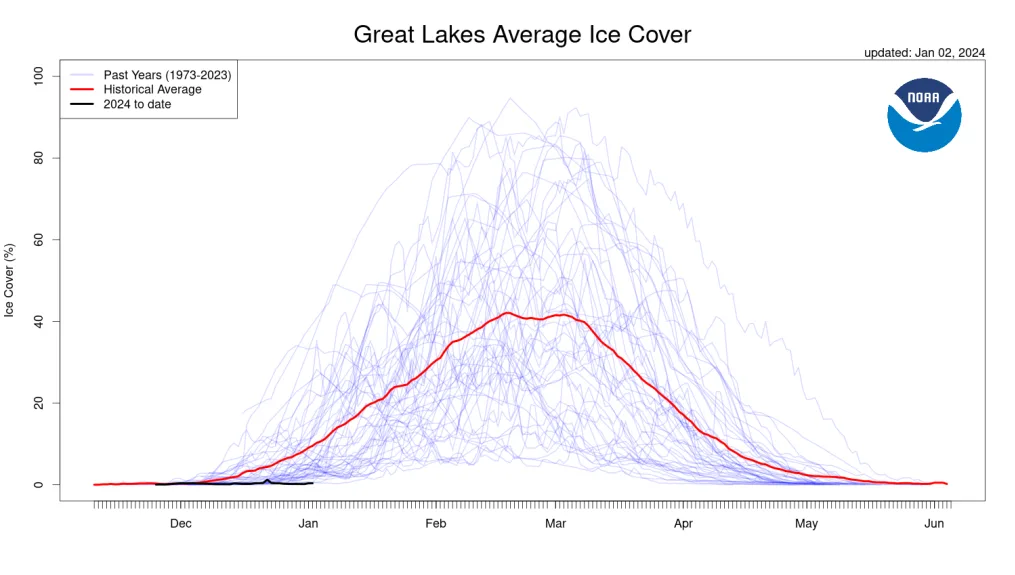

The Great Lakes, a cornerstone of North America’s natural landscape, are witnessing a startling environmental shift. As we stepped into the new year, these vast bodies of water presented an unusual sight – a stark lack of ice. With only 0.35% of their surface frozen as of New Year’s Day, they’re experiencing the lowest ice cover for this time of year in over half a century.

This record low, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL), is not just a fleeting anomaly but a signifier of deeper environmental changes.

The Current State of the Great Lakes

As we delve deeper, let’s paint a picture of what’s happening in the Great Lakes right now. The ice cover, or rather the lack of it, is alarmingly low. We’re talking about a mere 0.35% ice cover as the new year rolled in.

To put this in perspective, the historical average for early January hovers around 10%. That’s a huge gap! James Kessler, a physical scientist at NOAA’s GLERL, puts it plainly, “It’s certainly very low for this time of year.”

What does this mean in real terms? The Great Lakes are a barometer for regional climate trends. When they’re almost ice-free at a time they’re usually starting to freeze over, it’s a clear indicator that something’s off. Kessler points to the air temperature as a key player.

“We’ve had consistently above average air temperature in the region, and we haven’t had consistently cold days,” he explains. In other words, it’s been too warm for the lakes to turn into their winter ice rink selves.

The Science Behind the Decline

To understand the vanishing ice on the Great Lakes, we need to look at the broader picture. It’s like connecting the dots between regional climate patterns and the icy surfaces of these lakes. The science is clear: as temperatures rise, ice retreats. But it’s not just about a few warm days; it’s a trend that’s been building over time.

The Great Lakes region, particularly the Upper Midwest states, has been feeling the heat. December temperatures soared 8 to 12 degrees Fahrenheit above the norm. Cities like Chicago, Detroit, Green Bay, and Duluth witnessed their warmest December on record. This heat wave didn’t just bring in milder winter days; it directly impacted the lakes’ ability to freeze.

James Kessler from NOAA’s GLERL explains, “Cold air is needed to cool the water so the lakes can freeze. But with the climate rapidly heating up, warmer than average temperatures in the region are melting the chances for Great Lakes ice to form.”

Essentially, the lakes need a consistent spell of freezing temperatures to don their icy cover, and lately, those spells have been few and far between.

The Broader Impacts of Low Ice Cover

The story of low ice cover in the Great Lakes isn’t just about missing winter scenery. It has far-reaching impacts, touching everything from local industries to the environment. When we look at the big picture, the effects are both intriguing and concerning.

Boost to Shipping, Challenge to Recreation

On one hand, less ice could be a boon for shipping. The Great Lakes serve as crucial routes for commercial vessels, and open waters mean extended seasons and smoother sailing. Researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Superior are studying how this change could boost waterborne shipments.

As Kessler puts it, “The commercial shipping industry is like a multibillion-dollar industry, and so less ice cover is good for them.” But there’s another side to this coin. Coastal towns that thrive on winter recreational activities like ice fishing and hockey games might feel the pinch. Their economic rhythms are tied to the ice.

Environmental Guardrails Gone

Ice cover plays a protective role for the lakes’ shorelines. Without it, coastal areas become more vulnerable to erosion and flooding. High waves, no longer buffered by ice, can wreak havoc on these fragile edges.

Setting the Stage for Snowstorms

Then there’s the unique weather pattern known as ‘lake-effect’ snow. This happens when cold, windy conditions move over an unfrozen lake, creating intense snowstorms. Kessler highlights the recent events in Buffalo, New York, as an example. With more open water, such snowstorms could become more frequent and severe.

Erie & Superior In The Spotlight

Each Great Lake has its own tale to tell in this era of changing climates, with Lake Erie and Lake Superior offering striking examples.

Lake Erie’s Ice-Free State

Currently, Lake Erie stands out for being completely ice-free. This isn’t just a one-off event; it’s part of a trend. Kessler notes that Lake Erie has seen a decline in ice coverage of about 5% per decade. This trend is significant because Lake Erie, being the shallowest of the Great Lakes, typically freezes more easily than its deeper counterparts. The fact that it’s now ice-free is a stark indicator of how warm temperatures are affecting even the most susceptible of the lakes to freezing.

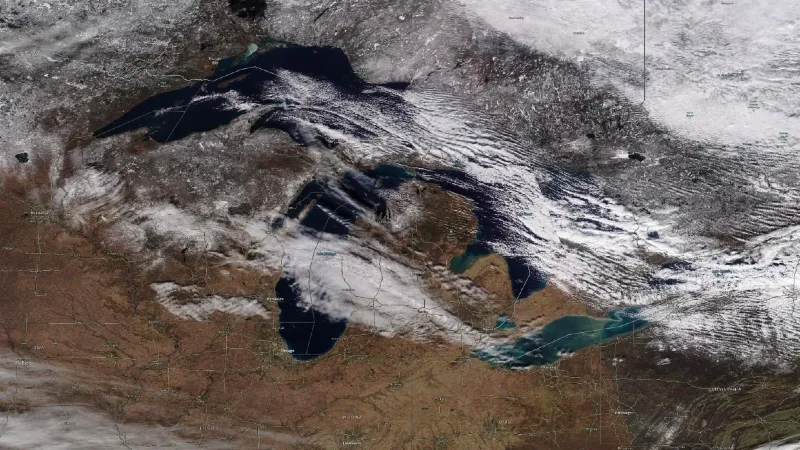

To put this into perspective, the following is a satellite image of Lake Erie taken by NASA on January 3, 2014.

Lake Superior’s Rapid Changes

Then there’s Lake Superior, the largest and deepest of the Great Lakes. It’s experiencing the most rapid rate of ice cover loss – about 7% every 10 years. Recent studies have flagged Lake Superior as one of the fastest warming lakes in the world. This rapid change is attributed to planet-heating pollution, altering the lake’s natural rhythms, and impacting the ecosystems within it.

These lake-specific trends are more than just statistics; they’re a reflection of how our global climate crisis is manifesting in localized ways, reshaping the natural landscapes we’ve known for generations.

Looking to the Future

As we turn our gaze forward, the future of ice cover on the Great Lakes holds both uncertainty and clear trends. Understanding these patterns is crucial for predicting how the lakes will behave in the years to come.

A Trend Toward Less Ice

James Kessler emphasizes the overall trend: a gradual decrease in ice cover. While yearly variations exist, the long-term trajectory points towards less and less ice. Kessler elaborates, “First of all, (the data) is very noisy. But if you fit a trend line to this data, you do get a decreasing trend, so we do see that (ice cover) is going down.”

This trend is consistent with broader climate patterns and is expected to continue as global temperatures rise.

The Role of Climate Variability

However, Kessler also cautions that it’s still early in the season, and a prolonged blast of Arctic air could change the current scenario rapidly. The peak ice cover in the Great Lakes typically occurs in late February or early March, indicating that there’s still time for significant ice formation, depending on weather patterns.

El Niño and Warmer Winters

The influence of phenomena like El Niño can’t be overlooked. Such climate patterns typically lead to warmer temperatures in the Great Lakes region, further tipping the scales against ice formation. As we experience a strong El Niño winter this year, the likelihood of continued low ice cover remains high.

Conclusion

Our journey through the changing ice cover of the Great Lakes has unveiled a complex and evolving story, one that intertwines with our broader climate crisis. From the record-low ice cover to start the year to the individual tales of lakes Erie and Superior, we’ve seen how these shifts impact not just the environment, but also the industries and communities that depend on these waters.

Here’s a recap of what we’ve uncovered:

More To Discover

- Historic Lows: The Great Lakes are experiencing significantly lower ice cover, reaching a 50-year record low this year.

- Warming Trends: Rising temperatures, partly driven by climate change, are the main culprit behind the decreasing ice cover.

- Mixed Impacts: The reduction in ice cover presents a mixed bag of consequences, from extended shipping seasons to heightened risks of coastal erosion and intense lake-effect snowstorms.

- Lake-Specific Changes: Lakes Erie and Superior demonstrate the varied impact of warming, with each showing concerning trends in ice loss.

- Future Uncertainties: While the long-term trend points to less ice, annual variations and factors like El Niño can still influence each winter season.

As we look ahead, the Great Lakes serve as a barometer for the health of our regional ecosystems and a bellwether for climate change’s impact. Understanding these trends is vital for adapting to a future where such environmental shifts may become the norm.

The story of the Great Lakes and their ice cover is not just about data and percentages; it’s a narrative about our planet’s changing climate and our response to these challenges.