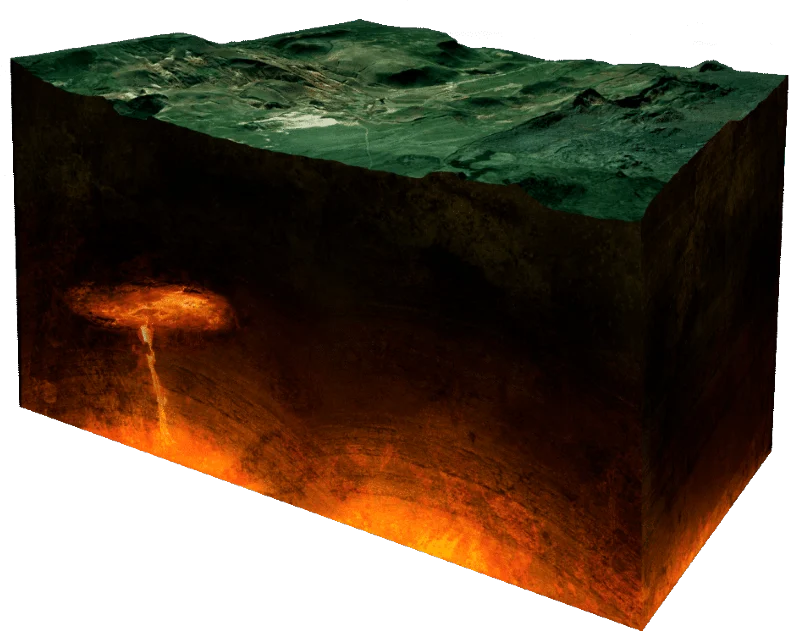

In a mission that seems straight out of a Jules Verne novel, Iceland is on the brink of an energy revolution. The Krafla Magma Testbed (KMT) project, set to commence in 2026, isn’t just a bold scientific endeavor but an adventure into the unknown. The goal? To drill into the magma chamber of an active volcano, tapping into the raw, super-heated power of the Earth.

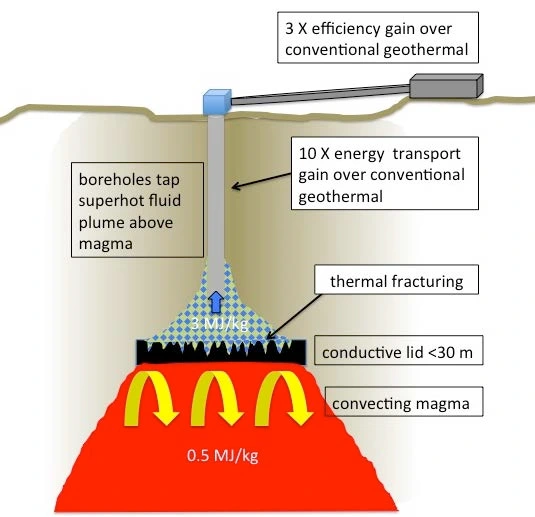

This initiative goes beyond conventional geothermal energy methods. Instead of just capturing steam from heated underground water, the KMT project aims to harness the intense energy of magma, the molten rock beneath the Earth’s crust.

According to volcanologist John Eichelberger from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, this groundbreaking operation at Krafla volcano won’t cause an eruption. It seeks to unlock a renewable and nearly infinite energy source, potentially powering homes across Iceland.

Geothermal energy isn’t new to Iceland, where 90% of homes are heated and 70% of energy comes from beneath the Earth. But tapping directly into a magma chamber? That’s uncharted territory. It’s never been done.

The KMT project plans to capture “supercritical” water — an extreme state where water is neither liquid nor steam — from the magma itself. This could yield a power output ten times greater than standard geothermal wells. In short, we’re talking a nearly limitless, all-natural power source.

The journey to Krafla’s core is fraught with challenges.

This project isn’t just about drilling deep; it’s about enduring extreme conditions. Krafla’s magma chamber lies only 1-2 miles beneath the surface, where temperatures reach a blistering 2,372°F (1,300°C). Drilling into this fiery abyss poses a unique challenge: creating drill bits and technology that can withstand such intense heat without melting.

This isn’t mere speculation — a similar feat was unintentionally achieved in 2009 when an Icelandic geothermal plant accidentally drilled into the magma chamber, offering valuable insights despite the destruction of the drill.

While drilling directly into the magma chamber in 2009 was a costly mistake (that drill wasn’t cheap), it did prove very valuable. Thanks to that error, scientists now know that drilling into a volcano doesn’t cause eruptions. It was that knowledge gleaned from an expensive drilling oversight that has allowed this project to move forward.

This wasn’t the first time something like this had happened.

The first documented case was at the Puna Geothermal Venture in Hawaii in 2005. At the time, from the energy companies’ point of view, exposing magma rather than hot steam was seen as a failure. That’s mighty ironic given how hard volcanologists tried to accomplish the same thing in years past. But later it became apparent even for the energy companies that the economic potential is immense.

As 2026 approaches, KMT scientists are rigorously testing materials to withstand these harsh conditions. Their success could unlock not only a vast energy resource but also groundbreaking tools for volcanic monitoring and eruption prediction.

More To Discover

- San Diego Man Makes History as First in U.S. Charged for Smuggling Climate-Harming Gases

- Is Vertical Agrivoltaics the Next Big Green Revolution, or Just a Passing Trend? A California Winery Is Going To Find Out

- Red Mud Goes Green: How a Simple Process is Turning Mining Waste into Climate-Friendly Steel

- The US Food Industry Faces Pressure to Reveal the Truth About Their Products

The KMT project isn’t merely an energy initiative; it’s a scientific expedition into uncharted territory. For the first time, volcanologists will have the opportunity to observe and study volcanic eruptions from their very source. This direct sampling of magma could revolutionize our understanding of volcanic activity, continental formation, and enhance geothermal energy technologies.

In essence, Iceland’s venture into the heart of Krafla is more than an energy project. It’s a leap into the future of renewable energy and a deep dive into the secrets of our planet. As Iceland gears up for this daring mission, the world watches in anticipation, ready to witness a potential paradigm shift in how we harness the Earth’s power.