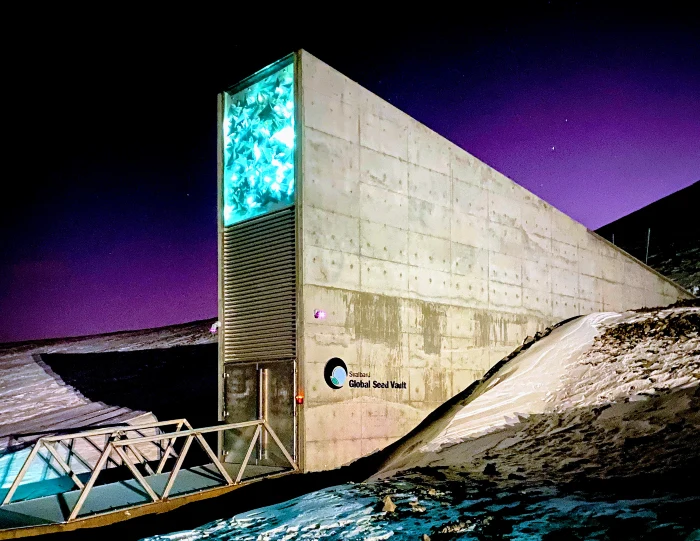

Picture the Svalbard Global Seed Vault: a frozen haven nestled deep within a Norwegian mountain, safeguarding our Earth’s diverse array of seeds. This impressive bunker, unveiled in 2008, carries with it an aura of hope reminiscent of ancient tales.

As Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg poetically expressed to an assembly of international representatives, this vault acts as “the modern-day Noah’s Ark, safeguarding biological diversity for the generations to come.”

Such notions might seem ripped straight from the pages of a science fiction novel. The concept of cryonics, or freezing oneself in hopes of a future revival, might come across as fantastical. While there have been wealthy individuals who’ve chosen to embrace this frosty chance at future life, they fundamentally rely on unprecedented scientific advancements yet to come.

But there’s an allure to preservation, especially in a time when our planet’s natural icy regions are dwindling.

In a groundbreaking move, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently proclaimed its collaboration with the nonprofit Revive & Restore, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance to establish a “genetic reservoir” comprising the DNA of America’s endangered species. As daunting challenges like climate change and habitat degradation loom large, dedicated professionals from the Fish and Wildlife Service are set to embark on “biobanking.” This process involves meticulously gathering genetic samples—be it blood, tissues, or reproductive cells—from creatures, then cryogenically preserving and genetically cataloging them.

Initially, the biobank will prioritize 24 species teetering on the brink of extinction, such as the Mexican wolf and the Sonoran Pronghorn, both pictured in the featured image above.

The hope is that this archived genetic material might one day serve as a beacon of rebirth, potentially enabling us to clone and resurrect species that might fade into oblivion.

Seth Willey, Deputy Assistant Regional Director at the US Fish & Wildlife Service’s Southwest Region, poignantly stated, “Through biobanking, we’re presented with an invaluable opportunity to conserve unmatched genetic diversity. If executed diligently, we’re essentially capturing a moment in time, empowering future biologists with revolutionary options like genetic restoration—options that hinge on proactive measures taken today.”

While this marks a pioneering foray into biobanking for the Fish and Wildlife Service, it also subtly hints at the impending trials these creatures are slated to face. The initiative evokes memories of cinematic adventures like Jurassic Park, or even the ambitions of Colossal Biosciences, which continually makes waves with its announcements of reviving extinct behemoths like the Woolly Mammoth.

However, there’s a crucial distinction to underline: while Colossal embarks on the arduous journey of reconstructing the fragmented DNA of bygone species, the Fish and Wildlife Service is harnessing the pure, untainted DNA of our contemporary fauna. Their efforts have already borne fruit with the successful cloning of Elizabeth Ann, a black-footed ferret, using cells preserved since 1988 (read more about Elizabeth Ann below).

In essence, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s endeavor more closely parallels the seed conservation at Svalbard rather than the dreamy aspirations of a frozen tycoon awaiting rebirth. This genetic vault serves as a testament to preservation, standing by, and ready for a future where its treasures might breathe life once again.

The Story Within The Story: Meet Elizabeth Ann

Spoiler Alert: She’s a Black-Footed Ferret!

“The Service sought the expertise of valued recovery partners to help us explore how we might overcome genetic limitations hampering recovery of the black-footed ferret, and we’re proud to make this announcement today,” said Noreen Walsh in December 2020. Walsh is Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Mountain-Prairie Region, where the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center is located. “Although this research is preliminary, it is the first cloning of a native endangered species in North America, and it provides a promising tool for continued efforts to conserve the black-footed ferret.”

The project sought to increase the genetic diversity among Black-footed ferrets – one of the most endangered mammals in the world, by creating a clone of a ferret who died over 30 years ago named Willa.

Willa’s genetically identical doppelgänger, baby Elizabeth Ann, was raised by a surrogate mother alongside other baby ferrets.

10 North American Animals That Should Be Preserved in the DNA Vault Immediately

The following animals represent a consensus from all the writer’s here at Dakoa. To be clear, no one asked us for our recommendations!

1. California Condor

Once on the brink of extinction, the California Condor is the largest bird in North America. Captive breeding programs have increased its numbers, but it remains critically endangered. There are currently around 334 condors in the wild and 203 in captive breeding projects.

2. Mexican Gray Wolf

Once extinct in the wild, reintroduction programs have begun to bring this subspecies of the gray wolf back. However, it's still one of the most endangered canids in the world, with only 241 wolves total. Forty packs for a total of 136 wolves are in New Mexico and 19 packs of 105 wolves in Arizona.

3. Black-footed Ferret

Native to central North America, it's one of the most endangered mammals on the continent. Disease and habitat loss have greatly reduced its population. According to the IUCN Red List, there are approximately 370 wild-living individuals in populations in several US states and Mexico, of which 206 are mature individuals in self-sustaining free-living populations. About 280 Black-Footed Ferrets are currently living in captive breeding facilities.

4. Florida Panther

A subspecies of the cougar, the Florida Panther is critically endangered, with only around 210–230 adults remaining in the wild. This big cat has had a long journey back from the brink of extinction in the last 50 years since it was first placed on the Endangered species list in 1967. The population has rebounded from an estimated low of only ten animals to over 200 animals.

5. Vaquita

As previously mentioned, this small porpoise in the Gulf of California is on the verge of extinction, primarily due to entanglement in fishing nets. In 2017 there were 30 remaining Vaquita, now in 2023 the population has dwindled to only 10.

6. Red Wolf

Native to the southeastern US, the red wolf is critically endangered due to habitat loss and hybridization with coyotes. Currently, only 15 to 17 red wolves roam their native habitats in eastern North Carolina, while approximately 241 are maintained in 45 captive breeding facilities throughout the United States.

7. Island Fox

Native to six of the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California, each island population is a unique subspecies that evolved separately from their mainland relatives. The past decades saw a severe decline in their numbers from habitat loss, predation and competition, and the introduction of diseases and parasites. Although conservation efforts have been successful, some populations remain endangered.

8. Northern Spotted Owl

This species resides in the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. Logging, severe habitat loss and competition with the barred owl have greatly affected its numbers. There are now fewer than 1,200 pairs in Oregon, 560 pairs in Northern California, and 500 pairs in Washington. Washington alone has lost over 90% of its old growth forest due to logging, which has caused a 75% decline of the Northern Spotted Owl population.

9. Alabama Beach Mouse

Found only in the dunes of Alabama, this small rodent faces threats from habitat destruction due to coastal development and rising sea levels. Beach mice play a vital role in the coastal dune ecosystem by dispersing seeds that stabilize dunes and serving as prey for predators. Furthermore, domestic (primarily domestic cats) and wild animals hunt them, while competition from other rodents has led to their decline in areas like Alabama.

More To Discover

- Wood Dust Solution Traps up to 99.9% of Microplastics in Water, A Potential Game-Changer Against Pollution

- JBS’s Greenwashing Charges As NY Demands Accountability For Company With Italy-Sized Emissions

- Heat Pump Sales Stalled by Labor Shortage, Says Industry Experts

- Bumpy Solar Cells? May Hold Potential for 66% More Energy Capture

10. Steller's Sea-Eagle

While primarily found in eastern Russia, this majestic bird occasionally makes its way to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The main threats to these rare sea eagles include habitat alteration from human development, industrial pollution, and overfishing, which in turn decrease their prey source. According to the IUCN Red List, the total population size of Steller's sea eagle is around 4,600-5,100 individuals, including around 1,830-1,900 breeding pairs.

These species represent just a portion of the many animals under threat in North America. Preservation efforts, both in habitat protection and initiatives like DNA vaults, are crucial to ensure their survival.